A written guide by Handdrawnbear

What is a line?

Lines don’t exist in nature, it is a two-dimensional construct of the mind in an attempt to understand and represent three-dimensionality.

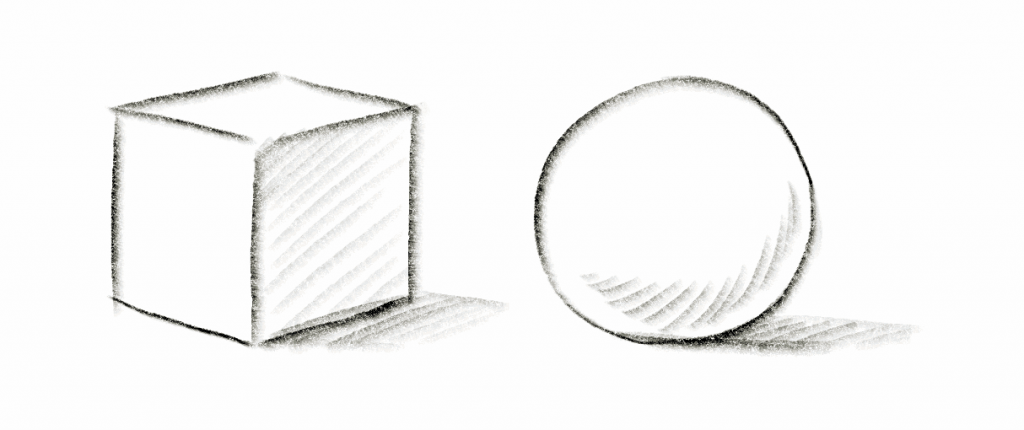

One might be tempted to think of edges as lines, that is how we describe a cube after all, but there are plenty of objects such as a ball, which has no edges, that also must be described by lines.

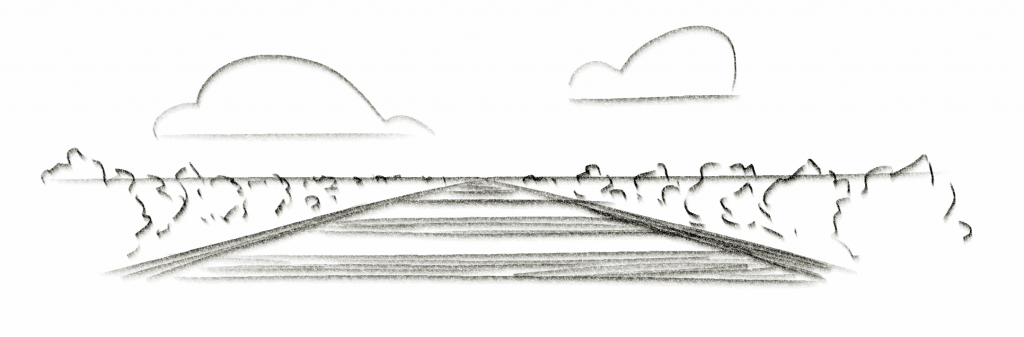

Lines are statements about where one surface ends and the next surface begins from our point of view. A line is used to define the limit of our perception, when an object or surface goes beyond our view; like the horizon line, it means we can see this much and no further.

How do we use a line?

It’s more a question of where, rather than how. Lines can be used to describe any object, but first, determine your level of magnification. How lines are used will differ whether we’re drawing a forest, a single tree, one branch, or just one solitary leaf.

We are informing the viewer where the edges of our perceptions are for this particular drawing, which will be defined by the level of magnification of the subject.

Drawing a forest means defining the edges and boundaries of the forest, therefore we must not concern ourselves with defining the edges and boundaries of each leaf.

Likewise, drawing a chicken means we can’t be tempted to define each feather; drawing a bear precludes us from focusing on every hair. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Handdrawnbear’s approach to drawing.

I can only speak for myself here, but the approach I take with any drawing is to use the least amount of lines possible, and start with the most important lines. Just as brevity is to wit, economy of lines is to a drawing. No one likes a line-salad of a drawing.

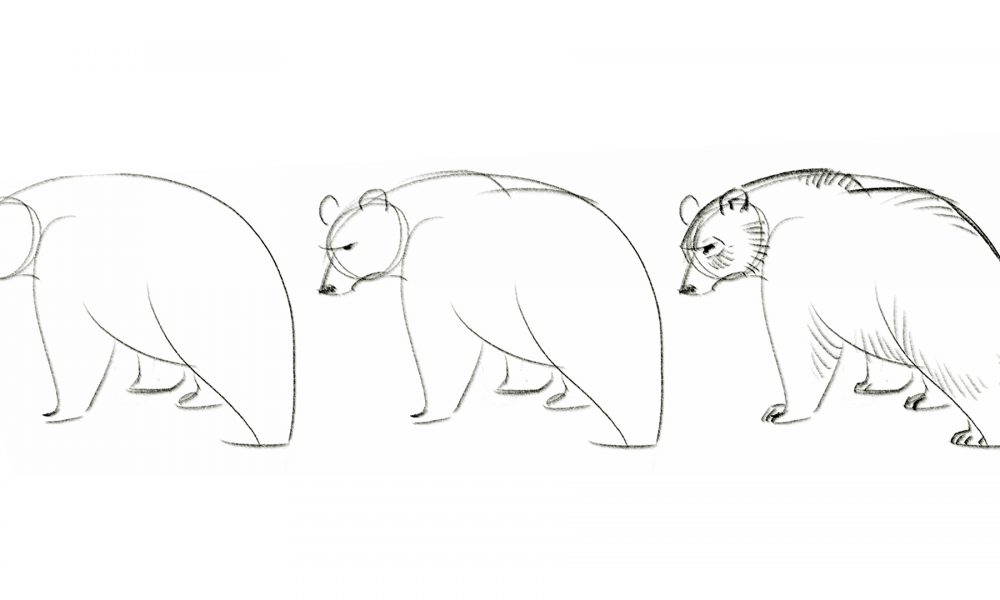

Let me explain. Say we’re drawing a bear, if you could only use one line to describe that bear, what would that line look like? I usually choose the line of the spine from nose to heel, which describes the posture of the animal.

Next, if you could only describe the bear using two lines, which line would you add? I’d put in the head in this instance. And then from there we continue to build the drawing from most important to least important lines, also known as drawing from the general to the specific.

This approach not only helps organize the drawing process, but also ensures that if we’re drawing from life and the subject moves or wanders away, we have put down as much essential information on paper as possible.

These methods have served me well over the years, and I hope you find them helpful, too.

-Handdrawnbear