Farming

Up On The Ridge With The Hogs

Wonderful writing from a cherished supporter of The Beartaria Times.

In the middle of the winter of 2018, a humble plate of pork sausage and fried eggs blew my mind. It was a game changer, as this was our first homegrown pork. Pork from a hog nurtured here on our land, by our own hands, from birth to harvest. We’d been enjoying the wonderful fruits of our hard fought garden for a few years, but this felt different. Not to veggie-shame at all, we cherish every bite of those too, but you know, it was just different. The gratitude I felt, and the gravity of the moment was overwhelming. What a crazy feeling! How on earth could a couple of former city dwellers, with no animal agriculture background, figure out how to raise our own meat? And why in the world did we choose hogs? Well, I’ll tell ya!

A couple years before that awe-inspiring plate, we had made the decision to uproot ourselves from the nonsense that had been brewing in the San Francisco Bay Area for a long, long time. We were done living like sardines, around people we couldn’t relate to. Our dreams were much bigger, including producing food for ourselves, on our own terms, without being regulated and scrutinized to death by people who had never raised so much as a tomato. So we set out, and just kept following the road North, as if we were being pulled in that specific direction. I’m guessing our shared Northern European heritage had activated some deep down ancestral magnetic pull to a land of harsh winters and endless challenges. Somewhere where we’d have to really earn that bountiful life, but when we did, it would be so, so sweet, and so worth it. Eventually we were guided to our little high desert oasis in southern Oregon, under the towering pines in the rural mountains above alfalfa country. Bingo. Home sweet home.

It’s not an ideal piece of farm land, by any stretch. It’s dry as a bone, hotter than heck during the summer, snowed in during the winter, with nutrient poor volcanic sand soil and only a roughly 90 day gardening season from frost to frost. No matter though, because it’s flat, it already had a well and a little house, and enough trees had been cleared to give us good sunlight and enough room to build. We decided the potential for what it could be outweighed the challenges of what it was. We planted ourselves, and declared we were going to bloom!

Mapping out the garden plot and chicken coop was first. It was the end of Summer already, but we’re not great at sitting still and wanted to get a jump on the next year. That first plot ended up being bigger than the footprint of our house, because hey, priorities. Within a week we had our first load of compost trucked in, and with the addition of a 100% necessary 8’ deer fence we were off and running for planting in the Spring.

The first step in animal husbandry, the obligatory chickens, came next. It took a few months for me to get up the nerve to actually commit to purchasing the first 6 little fuzzballs from the feed store. Like more prodding than it took to get me to OK our 2 Great Pyrenees puppies. Those little peeps were just so fragile looking and I was nervous, truth be told! We aren’t able to free range, though, given the amount of flying and digging predators, so the coop and covered run we had built were constructed like an impenetrable fortress, making my concerns just a tad overblown. So, that first little box of chicks came home, lived indoors in a makeshift brooder until they were fully feathered out, and all was well.

1 month after biting the bullet on the pullets, having built up the confidence that we could successfully care for livestock, the first 2 little female piglets were purchased. Just like that, we were hog farmers. The girls, a spotted one and a red one, were 2 month old, cute as a button little “weaner” piglets from a local family. Their breed mix is Red Wattle, Berkshire, and Duroc, which are all Heritage breeds. They’re a bit different than the common lighting-fast-growing pink or white pig you think of when you think commercial hog farming. Heritage breeds grow slower, and are more specifically bred for either higher quality “bacon” or “fat”. Lucky for us, the breed mix of the girls are suitable for both needs. A baby boar from another family was added to the mix about a month later, and all of a sudden we had all the necessary biological components of a small-scale homestead pork production operation.

The first 3 hogs quickly outgrew the first shelter and fenced off area we’d built for them. For a short while, we’d be woken up every morning to the sound of our quickly growing little boar jumping over the 4 foot wooden wall that was supposed to keep him inside his pen. Kind of blatant a sign that we needed to expand, so expand we did. As hogs get bigger and start breeding, it quickly becomes a matter of safety and comfort to be able to have separate areas for sows to give birth and to raise their piglets, away from the other adults. More and more fencing was installed, more specific areas defined, more shelters assembled. You end up getting to be an expert at those funky little wire clips that hold fencing to t-posts, rather quickly!

Piglets are magical little beings, like the cutest little velvet covered things ever. Definitely a bonus because they tend to show up on the coldest snowiest night, around 2 or 3 am. They have this innate ability to crawl out of their birth goo and find the life-sustaining nipple within a minute or so of being born. It’s really an amazing thing to watch. They’re fighters from the start and are ready to sustain themselves independently from Mom within a few weeks to a couple months. Over the years we’ve been able to sell off most of the almost 60 piglets born here to people in our community, but we’ve also kept a few who didn’t sell before the off-season, meaning our sheltering configuration has grown and changed numerous times. Flexibility and adaptability has been key.

Hogs sound like a ton of work, so why do it, you may ask? Good question. It’s quite a leap to go from a small feathered animal that can survive off the land if need be, to a small herd of behemoths that require significantly more input in the form of food, housing and and attention. We initially made that leap in faith, not really knowing what we were getting into, and have learned quite a bit since! Hogs aren’t cheap, they can be pretty destructive, they require a lot of room, and they will figure out every single weakness in that fence you thought you’d repaired faster than a gifted kid solving a rubik’s cube. All valid concerns, and all things we figured out through trial and error. So, what are the pros?

I’d have to say the number 1 factor in choosing hogs is the amount of meat you get from 1 animal, and the versatility of that meat. From the same hog, at butcher weight of about 280-300lbs, or 6-8 months old, you can plan on having 180-200lbs of meat, fat and stock bones. That’s enough for a couple, for a year. 2 hogs, which are easier and more fun to raise than 1 since they’re buddy-buddy type animals, will probably feed your whole family, for quite some time.

I can tell you, we haven’t bought meat from a grocery store in years. The myriad of different cuts of meat you get from a hog keeps us creative kitchen types constantly coming up with new dishes. Of course you have the delicious standards of bacon, ribs, hams, and chops, but there are also steaks in there, roasts, and endless, literally endless varieties of sausage. There’s a type of sausage, or ground pork, for almost every culinary whim, and every meal of the day, thanks to the worldwide variables in spice blend mixtures. Then you start thinking about things like pulled pork, schnitzel, meatballs, cured meats…ok, now I’m getting hungry.

What else? They’re hearty animals. Feed them well, including natural pest and parasite control measures, and health is almost guaranteed. Give them shelter with enough straw during the winter and a cool mud hole during the summer, and you’ll have a very happy hog on your hands.

They have great personalities! They’re goofy, and I’d argue they’re smarter than dogs. Now, that may be a deal breaker if you can’t bear the thought of butchering an animal like that. An animal that trusts you. Fair enough. You can also raise them at arms length and you’ll still get way better pork than you’d find at the grocery store. For us, though, it’s a much more comforting feeling knowing the animals we’re raising, with the ultimate purpose of harvesting, were given the absolute best life possible, with joy we’ve personally witnessed. And to know that for sure, we have to be very involved. Even up until the very last minute. We’ll be by his side and can say with certainty that there was no fear in his eyes. That means we harvest here on site. No shipping off to a final destination, alone and afraid. I can’t even imagine that. We feel that’s the least we can do for that hog as a thank you for the overwhelming abundance of nutrition that animal will provide us.

To get to that place of peace with the cycle of life and death wasn’t just an overnight thing. We worked up to it, for sure, and there’ve been many ups and downs. We’re currently over 3 years in, and on our 7th litter, which have been the most time-consuming and challenging to date. That’s a story for another time. That’s the thing, though. There will always be ups and downs and challenges. Do you give up? No. Giving up doesn’t even enter your mind at this point. You embrace those challenges, and you become stronger for it. Raising your own food is an entirely different thing than walking into a store and picking out packages, and it requires a whole new mindset. Or, maybe ironically, a return to a very old mindset. Cooking every single meal from scratch, and nurturing the ingredients you’re using for those meals, becomes multiple full-time jobs that you become happy to show up to day in and day out. Freedom really does require an incredible amount of responsibility! It’s hard, dirty, and sometimes unpleasant, but the rewards are worth it. Your first plate of homegrown sausage and eggs will definitely prove that!

-Breanna

@ameliaameliorate on Instagram

Farming

Cicada Shells Are Beneficial For Your Garden?

This post opens up many other interesting concepts, like fungal networks under our gardens…

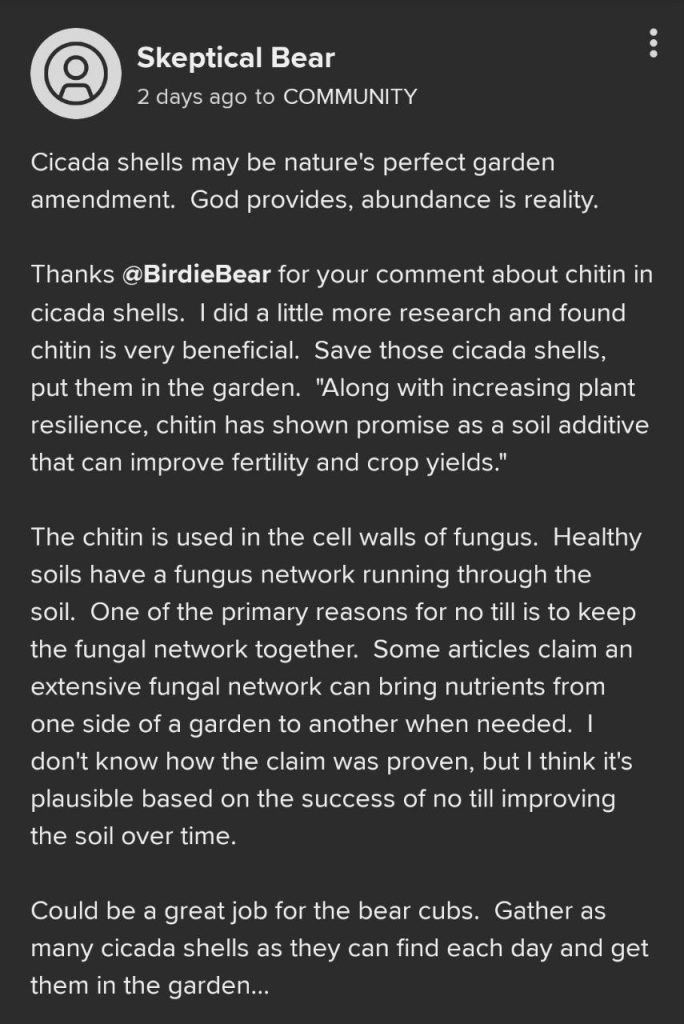

While scrolling our community app today, we came across an interesting post from Skeptical Bear, which exposed us to the idea of Cicada Shells and Chitin.

This post opens up many other interesting concepts, like fungal networks under our gardens, that we would love to hear more about!

Skeptical Bear went on to share some articles and cite his research,

https://www.shroomer.com/chitin-in-fungal-cell-walls/

https://pubs.sciepub.com/wjce/11/4/1/index.html

We haven’t dove into these articles yet so let us know what you think!

Farming

So, That’s Where That Saying Comes From!: Living the Phrases in my Beartaria

Living on a farm and living the phrases that come with it, you find yourself with lots of literal ‘Fences to Mend’ and ‘Gatekeeping’ to do.

By FruitfulBear

My dynamic shift from a lifestyle of apathy to a fruitful focus on the good, the true, and the beautiful came with a new awareness of the possible origins behind previously trite catchphrases. I started noticing and found myself greatly entertained and oddly fascinated with phrases and sayings I’d grown up with.

In the summer of 2020, I started making the notes that grew into this article. The first time I ever harvested blackberries from a bush, they grew in the front yard of the house I lived in with my mother and sister. Several bushes were growing next to each other, and the hedge they made was brambly and mildly daunting to my newly awoken yard working ability.

I wore sleeves that weren’t thick enough, gloves that weren’t thick enough, and there was a very low yield on these bushes I was harvesting from. At 33 years old, the only food I had ever foraged for was tangerines off a small, short tree at the side of my grandparent’s driveway. By comparison, these blackberries presented as a ‘Thorny Problem.’

I came inside after my earnest endeavors and presented my roughly two cups of blackberries to my family. Delighted with the ‘Fruits of My Labor,’ I grinned as I explained my new thoughts on the ‘Low Hanging Fruit’ concept. The berries, though few, were delicious, and the tangible way I found myself living the phrases that had previously meant so much less was going to ‘Bear Fruit’ of its own for years to come.

We moved to 5 acres in Idaho at the end of 2021 and, in short order, found ourselves getting chickens, goats, ducks, and a garden. It has been an adventure-and-a-half, full of many opportunities to crush and lots of phrases to live. From our chickens, I came to new understandings about the phrases:

- ‘Tough Old Bird’ – when harvesting old roosters

- ‘Cocky’ – the attitude of said roosters every day before they were harvested

- ‘All Cooped Up’ – the behavior of our flock on the rare occasions when we were forced to keep them in their roosting area all-day

- ‘Flew The Coop’ – when we let them out after being cooped up, there is simply no other way to describe them practically launching themselves out the door to get back into the sunshine

- ‘I’ve Got A Bone To Pick With You’ – when cleaning the chicken carcasses, separating all the meat scraps for soup

- ‘She’s a Good Egg’ – I decided this must be shorthand for laying hens that produce good, properly formed chicken eggs

- ‘Chickenshit’ – this insult doesn’t land quite the same after you’ve cleaned out the coop floor under a flock of roosting chickens

- ‘Pecking Order’ – the chickens were developing one of these long before you and your co-workers thought to

- ‘Not All It’s Cracked Up To Be’ – do I really have to explain this one

Now, if we move on for a moment to our ducks, ‘That’s a Whole Different Animal’ and ‘Like a Duck to Water,’ you can easily understand, if you are used to chickens by comparison, that ducks are a bunch of crazy ‘QUACKS!’ But, ‘Like Water off a Ducks Back,’ they don’t really care what the chickens are doing because ‘Birds of a Feather Flock Together.’

Living on a farm and living the phrases that come with it, you find yourself with lots of literal ‘Fences to Mend’ and ‘Gatekeeping’ to do. You ‘Travel The Well Worn Path’ to and from your barn all day. And, when you start finding hay and straw in more places than the sand manages to get to at the beach, you can’t argue against calling the feed bales ‘Flaky.’

When you’re trying to cut the ‘Ties That Bind’ on those same hay bales, and every single chicken that calls your barn home is demanding that you feed them their scratch grains, ‘Underfoot’ is definitely alive for you.

You’ll be tempted to ‘Cry Over Spilled Milk’ and find yourself turning the phrase ‘I’m Working Through It’ into a mantra of grit and endurance. The ‘It’ becomes muscle fatigue, headaches, or any other dis-ease in your life, physical or otherwise. You keep ‘Working Through’ because creatures big and small depend on you and don’t go away just because the work is more challenging to accomplish that day.

It becomes the highest of compliments when, at the end of a hot summer day after the sun has set, that first small breeze blows a whiff of cooling night air into the house, and you consider how nice it is to be compared to a ‘Breath of Fresh Air.’

Watering your garden as the strawberries, tomatoes, and other delectable produce start ripening enough to eat just a few before the full harvest, having ‘First Pick’ has never been more desirable.

Whatever temporary obstacles are between you and your Beartaria, I know you will ‘Get to The Root of the Problem,’ so just keep crushing.

I’ll end for now by wishing you all a ‘Crumby’ life since it means you got to have your ‘Daily Bread.’ And, I’ll ‘Level With You’ that I may reach out again in the future so we can ‘Chew The Fat’ while thinking about some more of our experiences as we live the phrases all around us.

Farming

How A Christian Taught Me To Slaughter Halal

While thinking of God’s judgment over me, my nervousness began to leave.

Reader discretion: This article discusses the processes of slaughtering lambs.

I begin with the name of The God, Most Gracious, Most Merciful.

So there I was, swimming in gravy and joy during the second annual Beartaria Times National Festival.

The bonfire roared and crackled, harmonizing with the diverse chatter of hundreds of people around the beautiful property. From outbreaks of laughter to questions that provoked silence and a subtle “woah” from engaged attendees meeting old friends for the first time, the atmosphere embraced you in a feeling of belonging, like a destination was found.

This destination, however, was not just the beautiful Missouri property but an environment manifested by all the legends that came with pure intentions, knowledge, wisdom, and guiding lights of family leadership, a meeting of lords and ladies from across the realm. Truly an elite class of prosperous minds and hearts.

The discussions were meaningful, and the light hearted humor was balanced with innocence and wit.

I had many moments of silence and reflection, smiling to myself as I felt the joy radiating from groups of legends around me.

While I had many valuable discussions, learned many things, and made many friends, one conversation made a huge impact on my life and assisted me in a 15-year-old goal and aspiration that seemed far from reality.

As I stood there, looking into the fire, having a moment to myself, I began to talk with an adventurous and inspirational legend.

He shared all kinds of experiences with me, from his long-distance marathons that I have always dreamed of pursuing to his experience as a high-profile chef, business adventures in Norway, and now his life of living in Missouri out of a converted school bus.

He began to tell me about his new venture of offering butchering services in Missouri. I was immediately intrigued and began to tell him about halal slaughter and my desire to be able to properly slaughter animals in accordance with Islamic requirements.

He comfortably and instantly resonated with it as he performs what he calls “Mercy slaughter”, a biblical slaughter that parallels Islamic guidance for slaughtering animals. I was super happy to hear this and saw the opportunity to ask all those questions I had about the preferred methodology of animal slaughter.

Almost 15 years ago, I began learning about halal slaughter. I found it fascinating and optimal for the animal and the consumer. It was instantly something I wanted to pursue. I never had the desire to do it commercially, but I wanted to be able to for myself, my family, and my wider community.

A little about halal slaughter and its requirements:

- The animal should have the name of God invoked over it during slaughter.

- The animal should be in a state of submission, mitigating all fear and pain.

- The animal should be slaughtered with one slice of the neck with a sharp blade. A clean cut without multiple cuts.

- The animal should receive food and water and be well kept.

- The animal shouldn’t be isolated or taken off alone to a strange place.

This process eliminates or minimizes the release of fear hormones like adrenaline and cortisol. Now, I don’t own a white lab coat, so I won’t pretend to know much about it. But the idea is that the animal goes out peacefully, respectfully, and is content. The process should be an act of worship and gratitude, invoking God over the animal to remember the source and reason for the sustenance that has been provided for you.

Having gratitude empowers the will to appreciate and take care of what you have been blessed with. Animals are amazing creatures, and it is our duty to be the best of shepherds and custodians over them. As a duty, there is accountability over us, and while we may not realize the accountability over us in this life, if we neglect to acknowledge it, we often find negative effects of it in our life.

So as I began the discussion of halal and mercy slaughter, I was happy to learn that the Butcher slaughters sheep and goats with a knife. He would lay them down, say a prayer, and efficiently slice their throats with one clean stroke.

This was what I wanted. I was well-studied in the topic but never met someone who does this, let alone regularly and comfortably.

I had all kinds of questions for him, like what kind of knife to use, the positioning of the cut, managing the situation, and seeing through the process of the animal bleeding out.

Not only was the helpful Bear able to answer all my questions, but he was also able to instill confidence in me to do it.

I expressed that I had 2 lambs at home that were being prepared for slaughter in the winter of 2023. After getting all my questions answered, I really started to feel prepared to take this on.

As winter approached after the festival, the lambs were really starting to look ready. My neighbor here in Idaho was also a huge help, working as a processing butcher for many years, a big-time hunter, owner of a taxidermy business as well. His shop has wolf hides, mountain lion hides, massive elk antlers hanging on the walls, and every tool you can imagine.

I reached out to let him know I was planning on slaughtering the lambs and how I wanted to do it. It wasn’t common for him to see it this way, but he is familiar with it and offered to help any way he can.

Leading up to the day, I was feeling nervous. I had the right knives, I knew what I was doing, but the nervousness was from the fear that I wouldn’t do right by the animal and thus not right under God.

I spoke to the helpful Bear again, and he played it all out for me, he even FaceTimed with me as he demonstrated positioning with his dog as a participant in the demo!

This really helped calm my nerves as he is such a matter-of-fact kind of guy. While not being a Muslim, he slaughters animals biblically, which is very much in line with Islamic direction. We bonded on the intention, the motive, and the blessing of what we have been provided.

The morning of the planned slaughter, my neighbor stopped by, which I wasn’t expecting. I thought I would just bring them to him after they were slaughtered. At first, it made me nervous again as there is someone watching me perform something I have never done before. Although I quickly remembered that it is God that I should fear and God that I remember as the one that I am accountable to.

While thinking of God’s judgment over me, my nervousness began to leave.

One of my longtime friends went into the lamb pen and herded them out the gate, at which point I grabbed the animal and steered it only about 15 feet to under a tree that they grew up by. At this point, my nervousness was completely gone.

We lifted the animal’s legs, laid it down on its side, and put enough pressure to keep it down. I began to pet the animal, being firm and comforting to the beautiful lamb I raised since it was little, jumping around my yard with joy. The lamb then went limp and showed me that it had submitted to its position and where it was. I then spoke in Arabic. “I begin with the name of The God, The God is the greatest”. I repeated this as I positioned my knife and when things felt right, I said it again and made the appropriate cut.

Leading up to it, I felt as though it would be a hard cut to make, imagining a thick hide and a lot of resistance; however, with a firm, well-intended cut, the knife passed through the correct position quite easily. Its neck opened up, and it was as if the animal went instantly unconscious, limp, and breathing deeply as the blood started to flow without any sporadic behavior. The blood spilled out consistently for about 1.5 minutes as expected, then the animal gave its final impulse kicks, and it was gone.

My neighbor was very impressed, saying how amazing it was to see the animal go so peacefully and how it was such a clean, well-managed situation. He repeated to me that the animal had such a peaceful, respectful death.

I felt great knowing that it was done to the best of my ability. I did my due diligence, and the guidance given to me was properly executed. It also felt great sharing this with my neighbor and him witnessing a halal slaughter, which even in a rural homesteading area is not common at all.

I had one more lamb, the male, which was always a little more powerful and brave than the female. I repeated the same process with a little more time spent on making it feel comfortable on the ground under me. Just like the first, the animal did submit and relax. I felt its temper slow down, its breathing slowed down, as though it said “fine, okay, I’m here and I submit”.

The process was just as smooth, and afterwards, seeing both these animals laid to rest, I stood up and felt as though I rose from prayer.

We then took the animals next door, and my neighbor helped me half them and put them in his freezer. He refused to take any money from me, saying something to the effect of ,

“I’m at a point in my life where the last thing I need is cash. I want to share these skills with the youth and anyone that wants to learn because these skills keep us free and thriving.”

While the internet can often be filled with debates, disagreements, elevations of self, and identities pitted against each other, my experience with two men of different faiths supported me in mine, not because of their endorsement of an identity label but because of the unity of truth. Truth that transcends labels, social opinions, or branded demographics.

While I have loved the Beartaria Times community since its inception, this whole experience has proved it is what it was designed to be.

Not a community based on the unity of identity, but unity of truth, sincerity, and aspirations for better lives for ourselves and for others. To respect and appreciate the diversity of each other’s opinions and thoughts to empower us forward, not as a wedge to prevent sharing things that matter.

Islamically, upon the birth of a child, it’s custom to slaughter an animal and to give 1/3rd away to family, 1/3rd to friends, and 1/3rd to the needy.

In December 2023, my wife and I celebrated the birth of our first child. Alhamdulilah!

I gave away one of the butchered lambs, to which I received so many great reviews. It was said that it was the best lamb people have ever had, the meat was so soft, picky children even asked for more!

It really inspired people to look into cultivating lambs or supporting me in escalating things.

In conclusion, I want to say thank you to the legend that helped with the amazing mentorship, thank you to my wonderful neighbor, thank you to the Beartaria Times festival team, thank you to The Beartaria Times and all the legends supporting it, thank you to the Big Bear for cultivating this community in a way where it is cultivating itself beyond the internet controversies and back to things that matter.

All praises to The All Merciful, The All-Powerful, Our Sustainer, and Our Provider.

-

Just Crushing2 weeks ago

Just Crushing2 weeks agoChristopher Gardner Completes First Dome Framing Project in Missouri: Exclusive Interview

-

Just Crushing2 months ago

Just Crushing2 months agoBeartaria Ozark Campground Launches Community Forum!

-

Just Crushing2 months ago

Just Crushing2 months agoMap it! – Discover Beartarians Living, Working, and Crushing Near You!

-

Just Crushing2 months ago

Just Crushing2 months agoWhy Do We Feel So Free?

-

Lifestyle2 months ago

Lifestyle2 months agoReconnect and Rejoice: Beartaria Times Weekly Challenge

-

Reports2 months ago

Reports2 months agoReport: EF-1 Tornado Touches Down In The Ozarks

-

Business2 months ago

Business2 months ago3000 Members In Our Business Group!: This Week On Our Community App!

-

Wellness2 months ago

Wellness2 months agoBeartaria Times Member Shares History and Benefits of Haymaker’s Punch